The EPA Actually Made America Great Again

My memories of the pre-EPA era are rusty, but vivid enough to know we don't want to go back there

Tariffs wiping out billions in assets, infectious disease specialists fired during life-threatening outbreaks and people struggling with addiction put on the street by executive order of the President—I totally get it if the gutting of the Environmental Protection Agency isn’t top of mind. That’s this regime’s mode: keep trolling us with fresh outrages—detaining university students without charges, say—so they can see what they can get to stick. Well, I’m trying to stay focused, people. For this week’s act of resistance, I’m sending a letter to every US Senator urging them to stop trashing the EPA. As dedicated by President Richard Nixon, its purpose was never to make buying a car cheaper, as its current lead, Lee Zeldin has said. It was to make sure we all have clean air to breathe, clean water to drink and prevent taxpayers having to pay for industrial excesses. Red tape and all, it’s been a huge success. My letter is a distillation of this post. Short on time? Use this link to express your own objections in seconds.

Nevermind the bow splash. The once badly contaminated Charles River, in Boston, is safe for a row or even a swim thanks to the Clean Water Act and EPA. Photo: Arnold Reinhold, 2018 Head of the Charles Regatta.

AGE SIX, I moved from Chicago to Boston with my mom and dad. Don’t remember much about the move; in fact, I recall three things: the soot-choked skies and paint thinner fumes of Gary, Indiana; the water bug that scurried under my sleeper sofa in Ohio; and the Sundance indie-worthy scene on arrival in Cambridge, where our new upstairs neighbor sat with her collie, Darby, tweezing engorged ticks out of her hide. Boy did I regret asking to see.

The memories improve from there. Met my friend Thomas in the second grade a few days later. We’re friends to this day. Made more friends in the apartments above and across the hall, too. We turned the building’s stairwell into a playhouse and theater set. The following summer brought the ‘75 Sox, a season to thrill any fan of baseball, much less a new one. (Yes, I do recall that home run: glimpsed through a cracked door, up past my bedtime but no one caring, my dad and his dad, visiting, leaning over the 10-inch black-and-white screen like the sonar in a submarine. My dad out of his chair and off his feet at 12:34 a.m.)

By the time I moved to California four years later, I had enough memories—the fall colors of Lexington, rags of snow in the dunes of Plum Island, three weeks of snow days post-Blizzard of ‘78—that it was easy for me to mythologize Boston. That’s what we kids who move around tend to do: Claim greatness for where we’ve been in order to bolster our specialness. If I’m honest, though, Boston has rarely lived up.

Yet in one respect it has steadily, dramatically improved since I lived there.

The Charles River has recovered and even flourished since the mid-70s when it was understood that while we might appreciate it’s coolness from the banks, we dare not touch it. This wasn’t only because I’d hadn’t yet learned to swim. This was because the river was then contaminated with toxic chemicals from local industries. It even looked sick at the shore, with sick yellowish piles of foam and eddies choked with cigarette butts and other debris.

Today, the Charles shines. It’s a body of water that, if you have a mind to, you can swim in—or, at least, dunk a coxswain in after winning a boat race without worrying about cancer rates. It’s a testament to how nature can recover if you stop messing it up so badly.

And the Charles isn’t that exceptional.

If you grew up in the 70s and 80s in the United States, I bet you can tell a similar story of riverine or marine revitalization—or of clearer skies, a brown field that’s now a dog park. If born in the 90s, you might wonder, what even was acid rain?

In Cleveland, where the Cuyahoga River caught fire repeatedly in the 50s and 60s, you can sit on restaurant deck today and enjoy a meal without gagging or burning. Bike paths, metropolitan parks, improved real estate values—the Cuyahoga is now an asset to far more people who live in Cleveland. It’s full of living fish. Some of them are safe to eat.

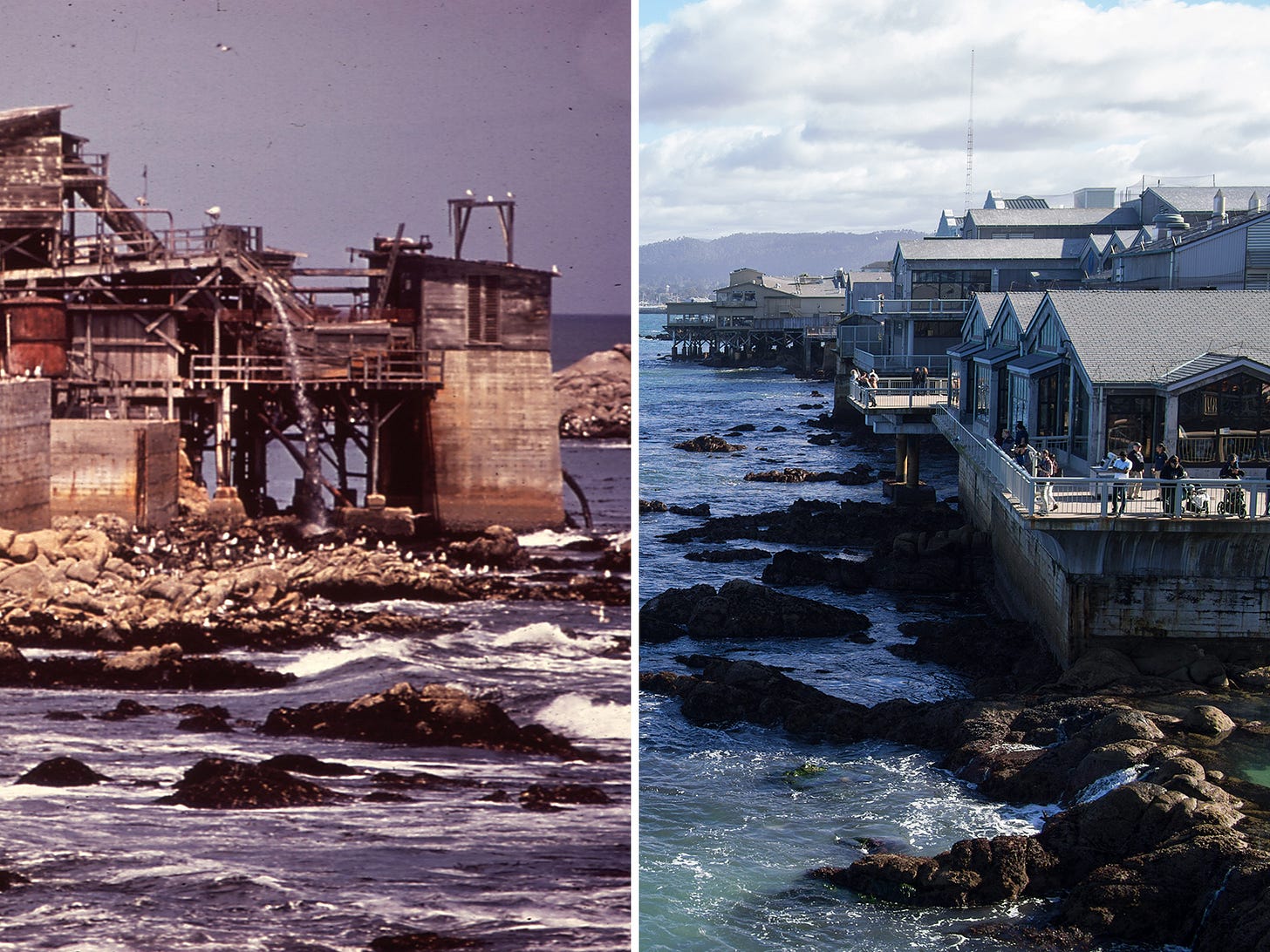

Though they parted long-ago, my folks somehow both ended up near Monterey Bay. In the late 1960s, it was an open sewer. Today, the impetigo and tetanus funk of Cannery Row has given way to a tidy, well-lighted promenade and a world-class aquarium. The region attracts four-plus million tourists every year and generates billions in tourism revenues.

The revitalization of Cannery Row, immortalized by John Steinbeck as “a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream,” began with the waters along it. Photos: Dick Rowan, National Archives and Records Administration; Rhododendrites/WikiCommons

In Alaska, the most valuable wild salmon fishery on earth has been protected from an open-pit mine. Bristol Bay hasn’t needed to be restored because it was spared from ruin.

And these are just a few examples of why the recent moves at the Environmental Protection Agency by its Trump-appointed director, Lee Zeldin, strike me as so very wrong.

Combined with the Clean Water and Clean Air Acts of 1972, the EPA truly made America great again. The agency has fulfilled President Richard Nixon’s vision for it—and then some. It’s helped restore natural systems we all need to thrive, but also created economic value where there had been harm and waste. Now, alleging massive corruption and massively exaggerating bureaucratic bloat, the Trump EPA is inviting industry to pollute again with impunity. Unless we all want to drink from the same tap as Flint, Michigan, their plans must be opposed.

A quick re-cap:

• On February 12, EPA lead Lee Zeldin cast the green bank program as a scam and froze $20 billion in federal grant money.

• On February 26, Zeldin said he’d slash the EPA’s budget by 65 percent.

• On March 11, Zeldin says he’ll terminate the green bank $20B altogether, though it’s not clear he has the authority to do so. (If I were still an assigning editor, I’d give this a hard look as it puts Citibank in the crosshairs, jeopardizes projects that Republicans in Congress fully supported, and—no doubt—will turn up some fraud, as well as progress, on climate.)

• On March 12, Zeldin announced the EPA will rollback 31 regs, including “reconsidering” controls on toxins like mercury; “unleashing” oil and gas operations (or did he really mean fracking wastewater?); and striking down the 2009 Endangerment Finding that established greenhouse gas emissions as a hazard.

• Also on March 12, Zeldin underling Jeffery Hall shot off a memo directing EPA staff not to enforce the “methane rules”—monitoring and policing oil and gas operations that leak natural gas. Methane traps 80x more heat than CO2 for the first ten years its in the atmosphere, so this blind eye to leaks is reckless and just plain stupid. As Mark Brownstein at the Environmental Defense Fund notes, “Oil and gas companies in the U.S. waste enough methane every year to supply natural gas for every home in the states of Texas, Pennsylvania and Michigan.”

• On St. Patricks’ Day, the New York Times reports on a planned “reduction of force”—1,155 EPA scientists—effectively the agency’s entire research division.

Zeldin’s number one talking point is that regulation “suffocates” business, thwarts prosperity.

The data say otherwise.

Regulations may lower the operating income of a few industries, but bigger picture, it’s more than worth it to have eco-cops on the beat…

• Every dollar invested in drinking water and waste water infrastructure increases the Gross Domestic Output by $6.35 over the long term – a 6 to1 return on the investment, according to the U.S. Conference of Mayors. And, as the American Society of Civil Engineer notes, “there’s no industry that does not need water.”

• Stricter regs on air pollutants from smokestacks, tailpipes, and pipelines—the very ones Zeldin et al want to eviscerate—could deliver $250 billion in net benefits annually, according to this 2024 report. That is, if you monetize the public health benefits of clean air, you find, for example, huge healthcare cost savings. Kids are not going to the ER with asthma, missing school so parents have to stay home, and so on. Plus, you know, your kid isn’t choking.

• Since 1970, emissions of common air pollutants decreased 77 percent while our economy more than tripled. These pollution reductions prevented more than 2.3 million premature deaths, 200,000 heart attacks, and 135,000 hospital admissions. They also prevented 17 million lost workdays.

Meanwhile, the US Census Bureau and US Department of Commerce, using 2005 data, found that what manufacturers spend on pollution abatement represented less than one percent of the $4.74 trillion value of the goods US companies shipped (pdf).

That’s not a small number, but it is not suffocation.

Could it be, as Trump-friendly trolls have it, that we no longer need a robust EPA because it’s job has been done?

This is naive at best.

“Without EPA on the job, we will be guessing at how much toxic pollution is in the water we drink and the air we breathe,” says Michelle Roos, executive director of the Environmental Protection Network, an association of 650 former EPA staffers who volunteer their time to continue its work. “We can’t go back to the days before EPA was formed when the skies were thick with harmful pollution and our rivers and lakes unsafe to swim in.”

Roos is a native of Pittsburgh, another city defined by its waterways and that has been transformed for the better since pollution regs got some teeth. It’s not something you need data to appreciate if you’ve spent time in Western Penn. Vigilance, she says, has been the only way to keep American cities like Pittsburgh clean; it only takes a few bad actors to ruin it for the many.

“Members of our organization, some of whom were with the EPA for 30, 40, even 50 years, say they have never seen anything like this,” Roos said of Zeldin’s cuts, which she described as “chaotic and vindictive.” Vindictive, she elaborated, because many of them target environmental justice efforts, or those intended to serve poorer neighborhoods that sit closer to sources of pollution. These “frontline communities” also tend to be, though are not exclusively, people of color. The moral thrust of EJ is that these residents, immediately downwind from refineries and incinerators, ought to get priority for once.

“This administration says it has a mandate to kill diversity, equity, and inclusion,” Roos said. “But what they’re actually doing is killing people because we’re not going to have safe water to drink or air to breathe.”

P.S. Don’t forget to write and call.

P.S.S. Feeling seen.